Most people are familiar with The Crusades, a series of religious wars initiated by the Catholic Church in the Holy Land between 1095 and 1291.

But few are as familiar with the most notorious crusade of them all: the Albigensian crusade, directed by Pope Innocent III. In 1209, he ordered Christian armies against fellow Christians in the south of France.

The catalyst was the Church’s determination to root out a heretical movement that had established itself in the Languedoc region in Midi France.

The heretics were known as the Cathars.

Ironically, the Cathars were probably a truer reflection of early Christians than the twelfth century church, which had by then become institutionalised. Cathar priests practised poverty and chastity in an age when many Christian bishops lived quite sumptuous and scandalous lives.

But the real challenge to the Church lay in the Cathars’ rejection of the physical world. They preached that hell wasn’t somewhere you went when you died. It was the place you arrived in when you were born.

They believed that the devil was the king of the world and God was pure spirit. The object of life was to escape it. Sex was a sin, not because it was pleasurable, but because it brought another soul into the devil’s domains.

The Church had been trying to eradicate the Cathars for over two centuries without success.

The murder of a Papal legate in 1208 gave the Pope the justification he was looking for.

To lure recruits for this unconventional military escapade, Innocent III offered a special indulgence to any nobleman who took up his cause. He gave them the sacred right to take ownership of any heretic lands they vanquished, along with the usual remission of all sins in the afterlife.

It also meant the crusaders did not have to travel far from home and only forty days of actual military service were required.

It attracted huge support in Northern France.

At the time, the Languedoc did not identify as French. The people spoke Occitan and had more in common with their neighbours in Catalonia than with the French.

Catholics, Jews and Cathars lived side by side with little religious discrimination.

So what happened next was virtually an invasion by a foreign power with the imprimatur of the Church.

The crusades against the Cathars began.

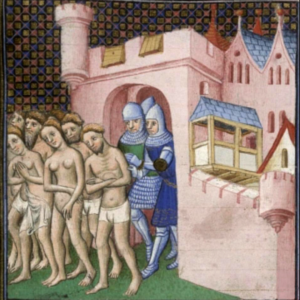

A legate named Arnaud Almaric was in command of the first assault against the town of Béziers in July 1209. It was largely a Catholic town, but it was sheltering a sizeable number of Cathars.

When they refused to surrender, Almaric ordered the annihilation of the city and its population.

He was supposed to have said, ‘Kill them all. God will know his own.’

It’s probably apocryphal, but it set the tone for the rest of the campaign. The soldiers under his direct command slaughtered everyone, including women and children.

The crusades against the Cathars continued for thirty years.

The so-called heretics who were captured were given the choice to recant or be burned at the stake. Few recanted.

The final siege took place at the mountain fortress of Montségur. Two hundred Cathar priests, or parfaits as they were known, burned to death under its walls.

Some historians – and it is hard to argue with them – consider the crusade an act of genocide. If that is what it was, it was an effective one. If it did not eradicate Catharism, it did drive it underground.

It was the impetus for the formation of the Medieval Inquisition, which terrorised Europe for hundreds of years.

FOOTNOTE: The crusade against the Cathars forms the backdrop to my novel Stigmata. It is one of the rarely visited tragedies of medieval European history.

Available on Amazon in Kindle ebook, paperback and in Kindle Unlimited.